One of the benefits of working for a high-tech automation supplier is getting to see how big, sturdy, and complex things in the industrial realm are built. My experience at ATS was that we routinely produced machines of great quality across the mechanical, electrical, and software spectrum. While part of that was my responsibility as an electrical and systems engineer, I also got to see how tooling, framing, fixturing, and various other mechanical assemblies were created. One of the raw materials we used most often is a product named extruded aluminum, or extrusion as we called it in short. Manufactured by companies such as Bosch Rexroth and 80/20 Inc., extrusion often served as structural support, as part of machine guarding, or as a mounting point for larger devices and components. I often liked to joke that we were the biggest consumer of extruded aluminum in Ohio, and that may not have been far from the truth from 2012 to 2017. Extruded aluminum gets a lot of use in industrial and scientific applications due to its lightweight nature (both from the aluminum itself and from its unique geometric profile), high strength-to-weight ratio, and considerable utility and ease of modification. While not necessarily the cheapest option for structural material out there, the benefits of using extrusion generally outweigh the costs if you want to make something strong, lightweight, and with plenty of room for attachments and tweaks.

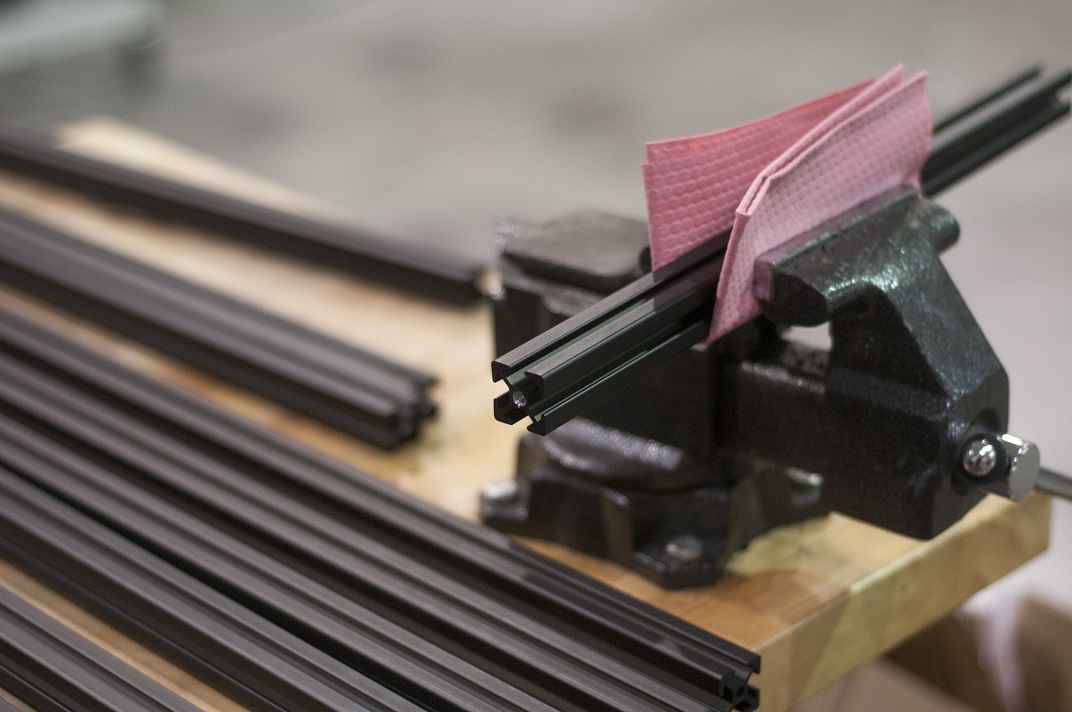

I had wanted to use extrusion in my own creations for a long time. After all, I was around the stuff on a daily basis and had free access to a huge amount of scrap material, so the only question was how would I use it. Actually, the more significant question is how could I get my wife to agree to let me use it in our own home. The profiles we used at ATS had a clear finish to them, which is the form of extrusion which most people encounter. The clear finish leaves the silvery color of the underlying aluminum exposed, which was not the most appealing for a home project. I agreed with my wife that the standard, silver profiles looked far too industrial to use outside of a workshop or garage, but when I discovered that 80/20 sold a version that comes anodized with a black coating in some smaller cross-sections, I finally got the OK to design and build some furniture.

I drew up a concept that would use some custom wood pieces and black-anodized extrusion to create a modern-looking coffee bar. We had recently been perusing over “coffee nook” cabinets and furniture to store all our mugs, coffee beans, grinders, presses, and other prep ware. Pinterest and Instagram offered many extravagant ideas for a home-made coffee bar design, but instead I designed something a bit more modest:

The frame itself used 25mm profiles that can accomodate M6 button-head screws, both in the T-slot channels and in the ends of each piece (after tapping the ends). I thought that the black finish would be more modern and aesthetically pleasing than any of the other styles; a conclusion that my wife agreed with when we actually received the material. The dimensions of the frame itself, 40″W x 34″H x 18″D, allowed for a standard, birch, ‘butcher block’ tabletop from a big box hardware store to be mounted on the top of the frame. The tabletop itself was trimmed down to have a consistent overlap on each side. In lieu of a stain or urethane coating, I treated the trimmed butcher block with a beeswax-infused mineral oil for food-safe protection. Two shelves, also made from birch pywood, were cut-to-shape and mounted on the inside of the frame, supported by black aluminum gussets. These shelves allowed for plenty of storage space for ceramics and glassware inside the frame. Leveling feet were installed in tapped holes on the bottom of the extrusion, which could be later replaced by casters, if I ever cared to splurge on them.

The unique structure of extruded aluminum allows you to choose between a number of attachment options. One could brace the cross-members with gussets, tap the ends to screw other fixtures onto the end face, or bore through the center to secure and suspend materials at a perpendicular angle to the long dimension of the profile. The downsides to using extrusion, like most any other metal framing material, come from the cost and from the unique requirements to manipulating the material. That said, if you have a drill with some sturdy bits and taps, and a sawblade capable of cutting through aluminum, then you have most everything needed to shape an extrusion frame. Most people would be surprised at how nice the finished product looks for being made entirely from industrial craft, in spite of the unique handling requirements compared to other chic-industrial materials like iron pipe.

Some benefits of building our coffee bar in this way were discovered much later. The ability to completely disassemble and rebuild the coffee bar without having to undo wood screws or loosen other fasteners proved hugely valuable when bringing it home. The channeled faces allowed for attachments to be mounted to the frame without power tools, and accessories like a plastic “channel fill” can be inserted to smooth out the look and feel of the frame. If we ever move (see the UPDATE), I should be able to break the coffee bar into enough pieces that it can be handled similarly to flat-packed, some-assembly-required furniture. Overall, the coffee bar looks fantastic in our home and the design is simple and sleek. The wife is really happy with it, so she gave me the green light to come up with more extrusion-based designs in future furniture projects!

UPDATE (3/4/2020): We have moved the coffee bar three times now (to and from Columbus, to and from Chicago, and now to Denver), and its actually the only piece of furniture we kept over all of our moves. This thing is still a fantastic piece of furniture, even many years after I originally built it!